The period around 1970 was marked by a clear turn in Tomasz Sikorski’s work. The composer focused entirely on exploring the phenomenon of sound as such. This change of viewpoint resulted in far-reaching modifications of his musical language, though we cannot say that this turn was revolutionary or resulted in a completely different direction for the composer. As we take a closer look at his sonorist works, the changes seem very natural, even obvious, undoubtedly stemming from the sensibility of the young, constantly experimenting artist.

Symptoms of the new can be found already in his Sonant for piano, on which the composer began to work when he was still in Paris, in late 1965. In this piece Sikorski still treats sound as purely physical matter. He plays with resonance (catching the fading sound of the strings with the piano pedal at the very last moment) and – as he writes in the Warsaw Autumn programme booklet – his aim is to break the sound matter into ‘two layers: attack and sustain’. Something similar happens in Diaphony for two pianos written in 1969: the composer listens to newly produced sound resulting from asynchronous playing of the same melody on both instruments.

Tomasz Sikorski must have realised that by just listening to the sound matter, no matter how fascinating and exceptional, he would not be able to write outstanding compositions. Works produced in this way could at best be ‘good’ or ‘interesting’. Sikorski needed an intellectual and firm foundation for his music, a foundation thanks to which he would be able to direct the listener to the essence of sound – its expressive depth. He, therefore, made use of what was very close to him: literature, literature and poetry. Holzwege for orchestra and Absent-Minded Window-Gazing for piano are his first compositions with literary titles and some of his most highly valued works. They crown his search, in them the composer discovers a new artistic mode of expression, both in piano music, with which he was so familiar, and in the much more extensive orchestral field. In addition, they constitute the essence of Tomasz Sikorski’s mature style.

For Strings (1970) as well as Absent-Minded Window-Gazing (1971) and Holzwege (1972) are an important point of reference in Sikorski’s work, because for the first time his objective in transforming much reduced musical material is to transmit non-musical content. The composer also tries to use to the maximum the expressive capabilities of his musical material, creating a wide range of sounds on its basis. In subsequent works this ‘model’ undergoes various transformations. They consist mainly in increasing the number of the structural elements (modules) of a work as well as their size and, consequently the size of the work itself, and in enhancing the variety of the musical matter used by the composer. In addition, Sikorski increases his efforts to maintain the substantive unity of his works.

Later, he will write more works revealing their programme or indicating the source of their literary or philosophical inspiration. Solitude of Sounds (1975), Sickness unto Death (1976), Afar a Bird (1981), The Silence of the Sirens (1986-87), Diario 87 (1987) are all works in which the composer symbolically presents a pessimistic vision of a lonely human being – that is himself. His other compositions from that period are full of tension, anxiety, sadness and despair as well. Sikorski oeuvre will never bring any hope.

In the 1980s, especially in his music for strings, the composer proved much more open to expressing feelings – they played an increasingly important role and became increasingly intense. This was associated with literary content referring directly to emotions being brought to the fore.

Works like Strings in the Earth from 1979-80, Winter Landscape from 1982, Recitativo ed Aria from 1983 and La Notte, written one year, later are highly lyrical. Sikorski enhances here the role of melody – it appears even in chord series. It becomes a new quality in Sikorski oeuvre, hitherto absent or present in vestigial form. Each of these works has at least one section in which we are dealing with an accompanied melody (with the accompaniment often provided by a solo instrument). What is also transformed is expression – feelings are often no longer suppressed or hidden; they erupt and the listener has to face them directly. Harmony, too, changes– Sikorski limits the role of his characteristic dissonances in favour of gentler, more consonant and euphonic sounds, which begin to predominate. Another element lacking here is violent expressive changes; in addition, there are decidedly fewer dynamic contrasts – each work becomes a sort of continuum, without any significant climaxes and clear formal divisions. The composer abandons his sonic experiments and exploration of the very nature of sound in favour of precise shading in of colours by means of slight harmonic modifications and various methods of articulation. Not only is this process not made difficult, but, on the contrary, it is facilitated by Sikorski’s homogenous line-ups and condensed chord or choral textures. As a result, even the smallest change is twice as emphatic in the listener’s perception. Sikorski still uses short modules, repetitions of which constitute a mechanism shaping larger fragments of his compositions.

Sikorski’s oeuvre has come full circle, it has been filled and fulfilled. We cannot help thinking that the composer may have sensed that the death was coming. It is possible that when he said all he had to say with music, when he decided that he had reached a dead end, when he no longer felt strong enough to work on new ideas, he came to the conclusion that his existence had ceased to make sense. These are only speculations, but Sikorski may have decided to end his life just like he decided to stop composing.

Owing to its aesthetic distinctness, Tomasz Sikorski’s oeuvre occupies a special place in contemporary Polish music. Its specificity stems from the modest range of technical means used by the composer and from more general phenomena: attitude to time and space, to hearing laws, to literary texts and subtexts, and, above all, the composer’s extraordinary sensitivity to sound. This sensitivity seems to have no parallel among contemporary Polish composers.

This is how Sikorski’s oeuvre is described by Ewa Gosman in her book. Andrzej Chłopecki, too, stresses the composer’s extraordinary sensitivity to sonic phenomena:

What was and remained the most important element for him was sound – acoustic object with its swelling and sustain, its vibration and flavour. What mattered most was an acoustic fact, sonic gesture, resonating phenomenon. It is as if he collected these phenomena and pinned them to paper – like others do with butterflies. Sikorski’s pieces have something of clusters in them.

Martina Homma has a similar view of the composer’s approach to the musical matter:

It is not the sound event itself, not what releases it and not its function in musical progression that seems the most important element in this music but the sustain, echo of the sound, its secondary impact no longer subjected to active impulses. Hence the meditative nature of these works, not directed forward but back and because of that – more than because of specific repetitions and pauses – not developing.

Tomasz Sikorski’s solitude was not only personal solitude caused by the absence of another human being. He was lonely also in musical, aesthetic terms. As Andrzej Chłopecki writes, Sikorski’s oeuvre:

was a lonely alternative to successive stylistic tendencies in Polish music leading not only to sonorism and not only to new Romanticism, but also to early pointillism, later return to folklorism, to new tonality. Sikorski never followed anyone else’s path – and no one followed his path in Poland. Hence the ambiguity of his presence, his lonely presence in Polish music.

Sikorski’s musical loneliness was associated primarily with a lack of understanding of his oeuvre, with its incorrect, superficial interpretations. It may seem incredible, but this extremely simple (when it comes to structure) and direct (when it comes to expressing senses) music was completely wrongly decoded my most.

It turns out that the simplest way to describe the music written by Tomasz Sikorski is to describe what is missing from it – though is it really true that what is absent from it is denied, negated? Development, seeking something, tension, culmination, dramaturgy, process. Memory is unnecessary as a tool of perception: it is difficult not to understand a piece that lends itself so easily to listening.

Andrzej Chłopecki points to an important issue relating to listening to and perception of music: habit. Accustomed to some patterns, we often reject what does not conform to them, what destroys the order of our world. Undoubtedly Tomasz Sikorski’s oeuvre destroys the order of the listeners’ world, their sense of security; it causes strange discomfort. Someone once said that development began two metres from the couch. It is worth abandoning one’s comfort zone and search for the truth. Sikorski’s oeuvre reveals the whole truth about him – the composer revealed himself in it as he really was, he did not hide anything, did not embellish anything, did not justify anything, did not explain anything. He told the truth and asked questions true answers to which were often unbearable.

Ewa Grosman, Tomasz Sikorski – zarys monograficzny twórczości [Tomasz Sikorski – a Monograph of His Oeuvre], Kraków 1992.

Andrzej Chłopecki [Tomasz Sikorski – rozpacz nagich dźwięków [Tomasz Sikorski – Despair of Naked Sounds] (unpublished)]

Martina Homma, “Polska muzyka na tle” [Polish music], Ruch Muzyczny 1989 no. 24.

Tomasz Sikorski’s oeuvre is much more extensive than people usually think. In addition to this best known and highly valued works, there is also a large group of less popular compositions which are yet to be properly recognised. There is also an unexpectedly large set of works which either have remained in manuscript form or the manuscripts of which have been lost, and we learn about their existence only from the composer’s accounts (mostly CVs and various forms in which he had to include lists of his works) or from other documents. In Sikorski’s case the lost manuscripts are not only, as often happens, those of youthful works, less appreciated by composers, works that make them slightly embarrassed or mortified, but also those of works he wrote as a mature artist.

In order to maintain chronological order, the list will open with his youthful compositions – i.e. those he wrote in high school or as a student – which have not survived. They are:

- Sonata for piano,

- Symphony for string orchestra,

- Triptych for piano (1955),

- Little Triptych for piano (1955),

- Five Miniatures for piano (1955),

- Reed Trio (1958),

- Variants for piano and four percussion groups (1960),

- Echoes I for piano and percussion (1961),

- Echoes II for five performers (1961-62),

- Sketches for string quartet (1962),

- Strettas for chamber choir and instruments (1962).

Later works that can be regarded as lost are:

- Musique Diatonique II for 20 wind instruments, 8 tam-tams and piano (1970),

- Etude for Orchestra (1972),

- Moderato Cantabile for cello solo (1986)

Works with unknown or uncertain dates of composition are:

- Two Etudes for orchestra,

- Four Pieces for Orchestra,

- Invocation for 28 wind instruments, choir, piano and chimes,

- Musica Concertante for piano and orchestra,

- Music for brass, tam-tams and chimes,

- Tabula Rasa for reciter, choir, two pianos and tape,

- Third Orchestral Piece for orchestra,

- Three Sketches for symphony orchestra.

Tomasz Sikorski may have also written, in 1971, Hommage à Kandinsky for orchestra. However, information about the piece can be found in just one, not very reliable source.

Most of the above manuscripts of works written after graduation were taken out from the Sheet Music Library of PWM Edition in Warsaw (at that time the Central Sheet Music Library) by the composer himself (between 1975 and 1983). Only the composer had the right to borrow (take out from the Library) deposited manuscripts on the pretext of introducing changes or corrections. Unfortunately, he never returned the manuscripts. He borrowed the biggest number of manuscripts (no fewer than six) on 18 April 1978. The causes behind both borrowing and not returning the manuscripts remain unknown. Sikorski never mentioned the situation to anyone. Nor was the situation exceptional. It was common for composers to make changes, corrections or prepare their scores for a new performance or edition. Of course this work was not done in the Library, but in the privacy of their home studios.

Sikorski was probably displeased with the pieces he took from the Library and wanted to withdraw them ‘effectively’. He may also – like in the case of Recitativo ed Aria and La Notte – have used substantial fragments of them in other compositions. However, owing to a lack of material for comparison, we cannot be certain of that.

After the composer’s death his apartment at Plac Konstytucji was cleared by the building manager without the presence of the family (Sikorski’s sister was still alive then). In such circumstances most of his personal belongings and manuscripts were probably lost. Sikorski spent the last few years of his life in solitude. He cut himself off from the world and did not let anyone near him. It is, therefore, difficult to say what really happened with the manuscripts. Did he destroy them before he died, during another mental breakdown? Did they end up in the dustbin in front of the building together with what remained of the furniture after the composer finished clearing the apartment of bugging equipment? We can hardly hope that they will ever be found. However, there is always a chance that a copy has been accidentally preserved somewhere.

Composing was a natural activity for Tomasz Sikorski. He watched his father, Kazimierz, at work and, like most children, tried to copy him. His mother, Helena, was Kazimierz Sikorski’s pupil, so the children must have inherited their musical talent from both parents. At the Sikorskis’ music – be it in the form of sheet music, records or live performances – was a constant presence. Tomasz Sikorski played the piano from a very early age and he must have improvised as well. Small pieces for piano, written while he was still in Łódź in the 1940s, were his first attempts at composition. However, he was ashamed of them and buried them to prevent them from getting into the wrong hands. According to Zygmunt Krauze, when Sikorski was still in high school in Łódź, he began writing Echoes, a piece directly inspired by the acoustic phenomenon. Later, when he transferred to a state music school in Warsaw, he and Zbigniew Rudziński took part in extra-curricular harmony classes conducted by Aleksander Jarzębski, a distinguished teacher and headmaster of the school at the time, who died tragically in a plane crash in 1962. As Zbigniew Rudziński recalls, the teacher organised a concert presenting the compositions they had written during those extra-curricular classes. It was in that period that Sikorski wrote the first pieces we know by title. The were written mostly for piano: Diptych – Pastorale e Toccattina, Triptych, Little Triptych, Five Miniatures, Five Preludes. All of them are dated 1955. Two of the Five Preludes were published one year later by PWM Edition, which must have been a great honour for the young composer barely on the brink of adulthood. The only other piece that has survived from that group is Diptych.

In 1956 Sikorski wrote three compositions which happily have survived to this day:

- Capriccio for piano and small orchestra, which the composer renamed Little Concerto before 1965,

- Song (Cantata, Canticle) of Wit Stwosz for soprano, choir of sopranos and chamber orchestra to words by Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński (published by Agencja Autorska in 1990) and

- Five Songs to words by Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński for voice and piano, which the composer offered to PWM Edition in 1986 after introducing some cosmetic changes.

The remaining works written by Sikorski during his studies at the State School of Music in Warsaw which have not survived are: Sonata for piano, Symphony for string orchestra, Reed Trio (1958), Variants for piano and four percussion groups (1960), Echoes I for piano and percussion (1961), Echoes II for five performers (1962), Sketches for string quartet (1962) and Strettas for chamber choir and instruments (1962). These are titles given by the composer himself, but we cannot rule out the possibility that Sikorski made some additional, less substantial attempts at composition in that period.

His surviving youthful pieces are characterised by a still traditional approach to the musical material. The composer uses bar notation on staves in these works, he does not use any non-standard ways of producing sound, but he does display considerable harmonic inventiveness. Sikorski presents himself as a skilful composer able to put his own ideas into practice. His scores are clear and the works are well-balanced. There is no mannerism, exaggeration or pushiness in them.

Tomasz Sikorski’s oeuvre acquired individual traits around 1963, when the composer made his Warsaw Autumn debut with Antiphons. The piece as well as most works written in the 1960s were part of the then dominant trend in music – sonorism. Sikorski drew on fashionable models, although from the very beginning his works had their own distinctive identity. The popularity of sonorism undoubtedly created favourable conditions for him. Referring to it, he could present his own, original approach to music, aimed at not only searching for new sounds and colours, but going also a step further, i.e. towards the nature, essence of sound.

At that time he was fascinated with several sonic phenomena like attack and sustain, swelling and fading of sound, resonance and flow of sound through space. His interests stemmed naturally from his sensibility. They were not a result of profound reflections, calculations or speculations. His artistic honesty was immediately noticed and appreciated. Young Tomasz Sikorski quickly managed to spread his wings.

The core of his oeuvre from that period is made up of five works (Antiphons from 1963, Echoes II from 1961-63, Prologues from 1964, Concerto Breve from 1965 and Sequenza I from 1966) written for orchestra or relatively large and varied ensembles. They always include the piano (or two pianos in the case of Prologues). In addition, the composer uses voices (choir and soloists) as well as sounds recorded on tape and processed in the studio. The multiple-page, dense scores of these pieces are markedly different from the very sparse notation used by Sikorski in his later, mature works.

The composer uses novel playing techniques and methods of sound production (e.g. enharmonic glissandos, ondulazione and vibrazione on brass instruments), as well as unusual instructions for performers, like playing the highest or the lowest possible note, touching the edge of a vibrating cymbal with a metal stick, striking with the piano fallboard, playing the piano with a ruler placed on its strings, slowly moving the bow over the strings in order to create a grinding effect or soundlessly pressing as many piano keys as possible.

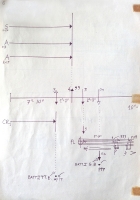

He very frequently uses non-standard tempo or time markings: gradual acceleration until the piece is played as quickly as possible (accelerando liberamente sino al più presto possibile) and gradual slowing down from playing as quickly as possible (ritardando liberamente dal più presto possibile), playing as quickly as possible (il più presto possibile), entering with a slight anticipation or delay, playing the same material in different tempi, specifying the time frame for a given fragment or duration of a pause. Usually, the principle of vertical synchronisation does not apply in works written in that period. In addition, the composer sometimes provides guidelines as to the layout of the performing forces.

Significantly, already in the 1960s Tomasz Sikorski organises the musical material in rows, putting together sound modules or making them overlap. The modules are created within uniform instrument groups: the woodwind, the brass, the strings, the percussion, the piano or the choir, which is always treated like a powerful homogeneous instrument.

Clashes of sound qualities, typical of sonorism, gradually give way in Sikorski’s works to a search for shared sound elements, a search for a shared sonic denominator for the various instrumental groups. Sikorski follows a direction opposite to the one followed at the time by most Polish composers, who focused on expanding the available sound palette, discovering new, hitherto unknown sounds. Instead, he seeks to discover the nature, depth and structure of sound – its ultimate cause.

This direction will determine his artistic path, which he will follow in a consistent and uncompromising manner. Bearing in mind the artistic choice made by the composer, we can easily understand why in his later works he seeks to reduce the musical material so much. The aesthetic foundation of such choices, their source and even sound effect are thus fundamentally different from the foundation of American minimalism, with which scholars used to associate some of the techniques used by Sikorski.

Sikorski definitely abandons sonorism in the early 1970s, though the turning point is by no means very clear. For example, in 1971 he wrote Vox Humana, a piece still rooted in the previous aesthetics. On the other hand, the composer ‘tested’ new ideas as early as in the 1960s, using the instrument he knew best, namely the piano. It has to be noted in this context that it was precisely the piano and its sound that had the decisive influence on the development of Sikorski’s musical language in every period of his work. In 1967 Sikorski wrote Sonant, a piece announcing radical changes. Short sound modules undergo slight transformations here, as if they were about to lose their distinctness, though at the same time they do not become similar. Sikorski’s aesthetic transformation is also heralded by Diaphony (1969) for two pianos, a work created basically of sound ‘snatches’. A bridge between the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ is provided by Homophony, a work written in 1968-69.

We are dealing here with a toning down of sharp contrasts, much lesser inner vibration of sound modules and greater focus on those sound qualities that bring together seemingly distant sounds. These elements begin to occupy a central place in the composer’s creative experiments.

Tomasz Sikorski won recognition already with his first compositions presented to a wider audience. They testified not only to his excellent knowledge of the secrets of composition, but also to his original approach to the sound matter. Sikorski’s music is directly derived from the composer’s fascination with the phenomenon of echo. In his works – both Echoes and Antiphons – he was interested primarily in the aspects of sound hitherto regarded as secondary. Music drawing on the echo phenomenon became a distinctive feature of Sikorski’s oeuvre.

This is how Andrzej Chłopecki commented on the appearance of the young composer in Poland in the 1960s:

In the orgy of clusters and murmuring sounds, sonic cascades and energetic percussion eruptions Tomasz Sikorski’s voice sounded different. It was not until ten years later, in the mid-1970s, that the aesthetics announced by Tomasz Sikorski – the aesthetics of minimal music – conquered the Warsaw Autumn stage.

Andrzej Chłopecki, Tomasz Sikorski – rozpacz nagich dźwięków [Tomasz Sikorski – Despair of Naked Sounds] (unpublished in Polish)

1955–1962

Sonata for piano

Symphony for string orchestra

1955

Five Preludes for piano

Diptych – Pastorale e Toccattina for piano

Triptych for piano

Little Triptych for piano

Five Miniatures for piano

1956

Capriccio (Concertino, Little Concerto) for piano and small orchestra

Song (Cantata) of Wit Stwosz for soprano, choir of sopranos and chamber orchestra to words by Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński

Five Songs to words by Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński for soprano and piano

1. Cemetery; 2. Night; 3. Lullaby; 4. Night II; 5. So simple

1958

Reed Trio

1960

Variants for piano and four percussion groups

1961

Echoes I for piano and percussion

1961–1962

Echoes II for five performers

1961–1963

Echoes II for 1, 2, 3 or 4 pianos, tape and percussion

1962

Sketches for string quartet

Strettas for chamber choir and instruments

1963

Antiphons for soprano, piano, French horn, chimes, 4 gongs and tape

1964

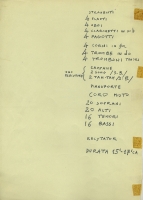

Prologues for female choir, two concertante pianos, four flutes, four horns and three percussions

1965

Concerto Breve for piano, 24 wind instruments and 4 percussions

1966

Monodia e Sequenza for flute and piano

Sequenza I for orchestra

1967

Sonant for piano

1968

Intersections for 4 percussionists (36 percussion instruments)

1968–1969

Homophony for 12 brass instruments, piano and gong

1969

Diaphony for two pianos

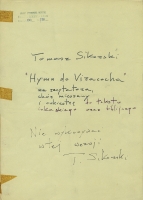

Hymn to Viracocha for reciter, mixed choir and orchestra

1970

For Strings for 3 violins and 3 violas

music to the ballet La Escala de Jacob (Jacob’s Ladder)

Collage for female choir, 28 wind instruments, 4 percussions, piano and tape

Musique Diatonique II for 20 wind instruments, 8 tam-tams and piano

1971

Vox humana (Voix humaine) for mixed choir, 2 concertante pianos, 12 brass instruments, 4 gongs and 4 tam-tams

Zerstreutes Hinausschauen (Absent-Minded Window-Gazing) for piano

Hommage à Kandinsky for orchestra

1971–1972

The Adventure of Sinbad the Sailor – radio opera for soprano, tenor, reciting voices, female choir and orchestra to libretto by Natalia Sikorska after Bolesław Leśmian’s The Adventures of Sinbad the Sailor

1972

Without a Title for piano and three optional instruments

Etude for orchestra

Holzwege for orchestra

1973

Listening Music for two pianos

1974

Music from Afar for mixed choir and instruments

1975

Solitude of Sounds for tape

Other Voices for 24 wind instruments, 4 gongs and chimes

1976

Sickness unto Death for reciter, two pianos, four trumpets and four horns to text by Søren Kierkegaard

music to the ballet A Traveller in the Belly of the Stars

1977–1978

Music in Twilight for piano and orchestra

1979

Hymnos for piano

1979–1980

Monophony for orchestra

Lontano for orchestra

Ostinato for orchestra

1980

Autograph for piano

Modus for trombone solo

Strings in the Earth for string orchestra

1981

Afar a Bird for clavichord or piano, recorded clavichord or piano and whispering voice to text by Samuel Beckett

1981–1982

Two Portraits for orchestra

1982

Winter Landscape for strings, Teodor Szczepański in memoriam.

Euphony for piano

Modus, solo cello version

1983

Recitativo ed Aria for strings

Autoritratto per Due Pianoforti e Orchestra (Self-Portrait) for two pianos and orchestra

1984

Rondo for piano

Invocation for organ

La Notte per Archi (Omaggio a Friedrich Nietzsche) for string orchestra

1986

Moderato Cantabile for cello solo

The Silence of the Sirens after Franz Kafka (Das Schweigen der Sirenen nach Franz Kafka) for cello solo

1987

Omaggio per Quattro Pianoforti ed Orchestra in Memoriam Jorge Luis Borges for four pianos and orchestra

Quintet for strings and piano

Diario 87 for tape and reciter to textby Jorge Luis Borges

Works with unknown or uncertain dates of composition

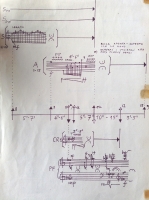

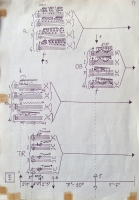

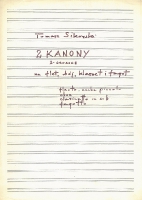

Two Two-Voice Canons for flute, oboe, clarinet and bassoon

Two Etudes for orchestra

Four Pieces for Orchestra

Invocation for 28 wind instruments, choir, piano and chimes

Musica Concertante for piano and orchestra

Music for brass, tam-tams and chimes

Tabula Rasa for reciter, choir, two pianos and tape

Third Orchestral Piece for orchestra

Three Sketches for symphony orchestra